Introduction

Parents say they are largely aware that their children play video games, but their engagement varies when it comes to knowledge of ratings, their steps to stop their children from playing, and the act of playing games with their children. While most parents attempt some form of monitoring, the parents of boys and younger children are more likely to monitor game play than parents of girls and older children. Most parents say they regularly check ratings and that certain games draw particular attention. And many parents say that on occasion they stop their children from playing certain games. Far fewer parents say they actually play video games with their children. The age and gender of the teen are consistent predictors of the amount of parent-reported monitoring.

A majority of parents are aware that their children play video games.

Almost nine out of ten (89%) parents say their children play video games (a considerably smaller number than the 97% of teens who self-report playing video games). More black parents (96%) say their children play video games than white (89%) or Hispanic parents (86%).

Parents of boys are more likely to say their kids play video games than parents of girls. Fully 97% of parents of boys say their sons play video games, compared with 81% of parents of girls. These numbers are quite different from what kids themselves report—99% of boys and 94% of girls say they have played a video game.

Parents know what games their children play—at least some of the time.

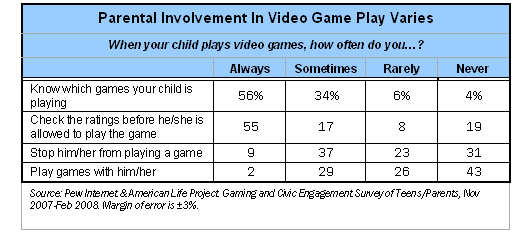

Nine out of ten parents say they sometimes or always know what games their children play, compared with 10% of parents who say they rarely or never know what games their children play. Parents of younger teens pay more attention to the games their children play than parents of older teens. Fully 63% of parents of 12- to 14-year-old teens say they always know what games their children are playing, compared with 48% of parents of 15- to 17-year-olds.

Girls ages 15-17 are the least likely to have parents that know what games they play: 42% of parents of girls ages 15-17 say they “always” know what games their daughters play, compared with 52% of parents of boys ages 15-17, 62% of boys ages 12-14, and 65% of parents of girls ages 12-14.

Teens with black parents are less likely to report that their parents know which games they play (79%), compared to teens with white parents (90%).

More than half of parents report “always” checking video game ratings.

Many parents are aware of video game ratings and check the ratings of the games their children play. More than half of parents of gamers (55%) report “always” checking the rating before their children are allowed to play a video game, compared with 17% who say they “sometimes” check, 8% who say they “rarely” check, and 19% who say they “never” check. Younger parents and parents of younger children (populations in which there are significant overlaps) are also more likely to say they “always” check the ratings of the games their children play than older parents. Among parents of teens ages 12-14, 80% ever check the rating of games their child play, compared to 64% of parents of teens ages 15-17. Two-thirds (67%) of parents under 40 say they “always” check the ratings of the games their children play, compared with 50% of parents 40 or older.

Gender also plays a role in the likelihood of parents checking the ratings on a game their child plays. Among parents of boys, 77% report ever checking the ratings of the games their child played, compared to 67% of parents of girls.

Parents of boys are more likely to intervene in game play than parents of girls.

Parents are split in how often they stop their children from playing a game.50 Fully 46% of parents say they “always” or “sometimes” stop their children from playing video games, compared with 54% who say they “rarely” or “never” stop their children from playing video games.

Parents of boy gamers are more likely to report that they always or sometimes stop their children from playing a game than parents of girl gamers. Eleven percent of parents of boys who play games say they always stop their sons from playing a game, and 42% say they sometimes stop their sons from playing a game, compared with 6% of parents who say they always stop their daughters from playing a game and 31% of parents who say they sometimes stop their daughters from playing a game. Overall, 53% of parents of boys report ever stopping their children from playing a game, compared to 37% of parents of girls. Previously, we noted that boys are more likely to play M- or AO-rated games than girls. The higher level of parental monitoring of boys is correlated with the fact that boys are more likely than girls to seek out games with content that is inappropriate for their age group.

Few parents play games with their children.

Media research suggests that when they participate in a media form with their children, parents are able to impart their values and beliefs about the acts and messages within the media form. This holds for watching television programs as well as for playing video games.51 Parents who play video games with their children can explain and contextualize the violent or negative messages that children might pick up from playing certain games.

A very small number of parents say they regularly play games with their children. Only 2% of parents say they always play video games with their teenaged children, compared with 29% who say they sometimes play games with their children, 26% who say they rarely play games with their children, and 43% who say they never play games with their children.

Fathers are more likely than mothers to report playing games with their children. One-third (33%) of fathers say they play games with their children sometimes, compared with 26% of mothers, and 30% of fathers say they play games with children rarely, compared with 22% of mothers. Over half of mothers (51%) say they never play games with their children, compared with 34% of fathers.

Younger parents (under age 40) are more likely than older parents to say they sometimes play video games with their children. Four out of ten younger parents (40%) report this, compared with 25% of older parents. Parents of younger teens are also more likely to engage in co-play. Among parents of teens ages 12-14, 34% play games with their child, compared with 27% of parents of teens ages 15-17.

Parents are unlikely to emphasize the impact of video games on their own children.

More than six in ten parents (62%) say that video games have no effect on their children one way or the other, compared with 13% of parents who say that video games have a negative influence on their children, 19% who say video games have a positive influence, and 5% who say video games have some negative influence and some positive influence —but that it depends on the game.

Parents of girls are more likely to say that games do not have any effect on their children than parents of boys. Seven in ten parents of girls say that playing video games has not had much effect one way or the other on their daughters, compared with 56% of parents of boys who say similar things about the effect of playing video games on their sons.52

Parents of male gamers are more apt to say that games have affected their sons negatively. Almost one-fifth (18%) of parents of male gamers say that playing video games negatively influences their sons, compared with 7% of parents of female gamers. This is especially true with regard to younger sons. Some 21% of parents of boys ages 12-14 say video games have a negative influence on their child, compared with 16% of parents of boys ages 15-17, 6% of girls ages 12-14 and 6% of girls ages 15-17.

Parents who tell us their children do not play video games tend to believe that video games have a negative influence on children. Over half of parents who say their children do not play video games (58%) say that video games are a negative influence, compared with 4% who say video games have a positive influence, 27% who say they have no effect one way or the other, and 8% who say it depends on the game.