Europe’s religious landscape is changing: The Christian share of the population is declining while the religiously unaffiliated population is increasing. In addition, Muslim populations in Western European countries continue to grow in both absolute and percentage terms due to immigration, relatively high fertility rates, and a relatively young population. Jewish populations, meanwhile, appear to be declining.

Against this backdrop, the survey sought to gauge public opinion on Muslims and Jews, immigrants and immigration, and nationalism and national identity. Beyond exploring overall public perceptions of these issues, the survey also provides opportunities for statistical analysis to help illuminate some of the social, political and cultural factors associated with views on pluralism and multiculturalism.

Overall, most people across the region express positive and accepting views of religious minorities, saying that they are willing to accept Muslims and Jews in their neighborhoods and in their families. Majorities of the population in each of the 15 countries surveyed do not agree with negative statements about Muslims and Jews, such as, “In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious law on everyone else,” and “Jews always pursue their own interest and not the interest of the country they live in.”

Still, undercurrents of discomfort with multiculturalism are evident in Western European societies. For example, across the region, people express mixed views on whether Islam is compatible with their country’s values and culture. Most Europeans support at least some restrictions on religious dress for Muslim women. And public opinion is divided on whether it is important to be born in a given country, and to have ancestry in that country, to truly share the national identity (e.g., to be born in France to be truly French, or to have a Dutch family background to be truly Dutch).

Attitudes on nationalism, immigration and religious minorities are closely connected with one another. For example, those who say Islam is incompatible with their country’s values and culture are also more likely to favor restricting immigration. And those who express negative views of Muslims are also more likely to express negative views of Jews. These associations allowed researchers to combine 22 individual questions probing these views into a 10-point scale of Nationalist, anti-Immigration and anti-Minority views (NIM). The higher an individual scores on the scale, the higher their nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-minority sentiment.

Generally, most Western Europeans tend to score on the lower half of the NIM scale (less than 5 points out of the possible 10). But there are wide variations by country: Italians are especially likely to score above 5, while Swedes score lower, on average, than people in any other country surveyed.

Other than what country people live in, various factors are associated with relatively high NIM scores. Researchers conducted advanced statistical analysis of the scale, considering the effects of age, gender, religion, education and several other factors one by one, holding all others constant. The results show that both church-attending and non-practicing Christians are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to score high on the NIM. That is, Christian identity – irrespective of level of religious observance – is associated with higher levels of nationalist, anti-immigration and anti-religious minority sentiment.

But religion is not the only factor associated with NIM scores: College-educated people and those who personally know a Muslim score significantly lower on the NIM, relative to those with less education and those who are not personally acquainted with a Muslim. Conversely, those who profess right-wing political ideology score significantly higher than those who lean left.

This chapter walks individually through survey results on more than 20 questions pertaining to the themes of nationalism, immigration and attitudes toward religious minorities, presenting descriptive findings at the national level. Question wording and response options are explained for each question. The chapter then goes on to discuss the results of the NIM scale and the factors associated with scoring high on the NIM.

Nationalism

Western Europeans take pride in both their national identity and European identity

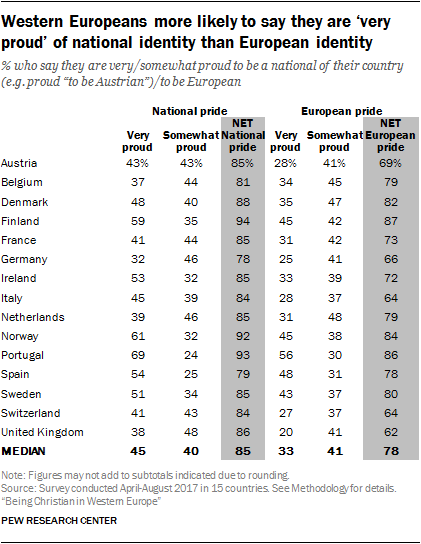

The survey asked people how proud they are of three possible elements of their identity: their national identity, their European identity and their religion. Respondents could select “very proud,” “somewhat proud,” “not very proud” or “not proud at all.”

National pride is widespread in Western Europe, with large majorities in every country saying they are either “very” or “somewhat” proud of their nationality (e.g. proud “to be Austrian,” proud “to be Belgian”). This includes at least nine-in-ten respondents in Finland (94%), Portugal (93%) and Norway (92%) who express national pride in this way. Germans are less likely than people in most other countries to say they are very proud to be a national of their country (32%), but most (78%) say they are at least somewhat proud to be German.

While most Western Europeans also express pride in a shared regional identity, more respondents express high levels of pride in their nationality than in being “European.”

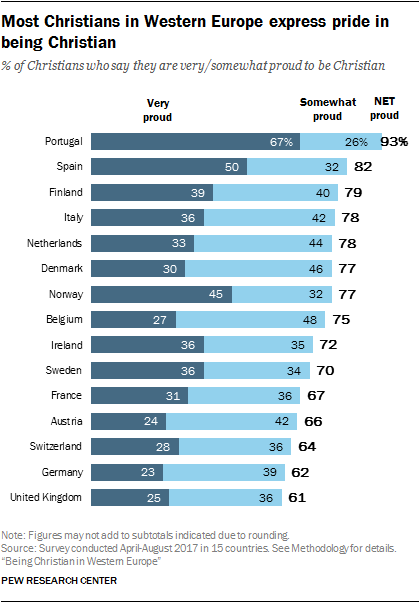

Majorities of Christians in every country surveyed say they are at least somewhat proud of being Christian. This includes vast majorities of Christians in the Iberian states of Portugal (93%) and Spain (82%), which also have among the highest shares saying they are very proud to be Christian (67% and 50%, respectively). By contrast, about a quarter of Christians say they are very proud of their religious affiliation in Belgium (27%), Austria (24%), the UK (25%) and Germany (23%).

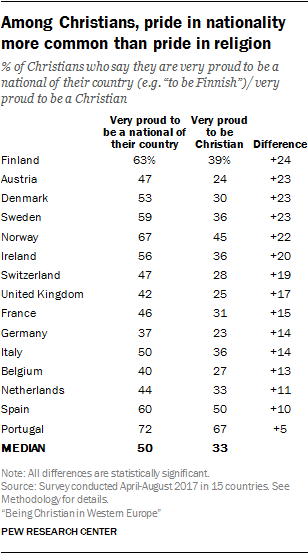

In general across the region, Christians are more likely to express high levels of national than religious pride. For example, in Ireland, a slim majority of Christians (56%) say they are very proud to be Irish, compared with 36% who are very proud to be Christian.

The survey also asked respondents who identify as atheist or agnostic whether they are proud of their religious identity; roughly half or more in nearly every country surveyed say they are at least somewhat proud to be atheist or agnostic, including two-thirds or more in Portugal (79%) and Spain (68%). (People who said they have no particular religion were not asked this question.)

What does it take to be one of us?

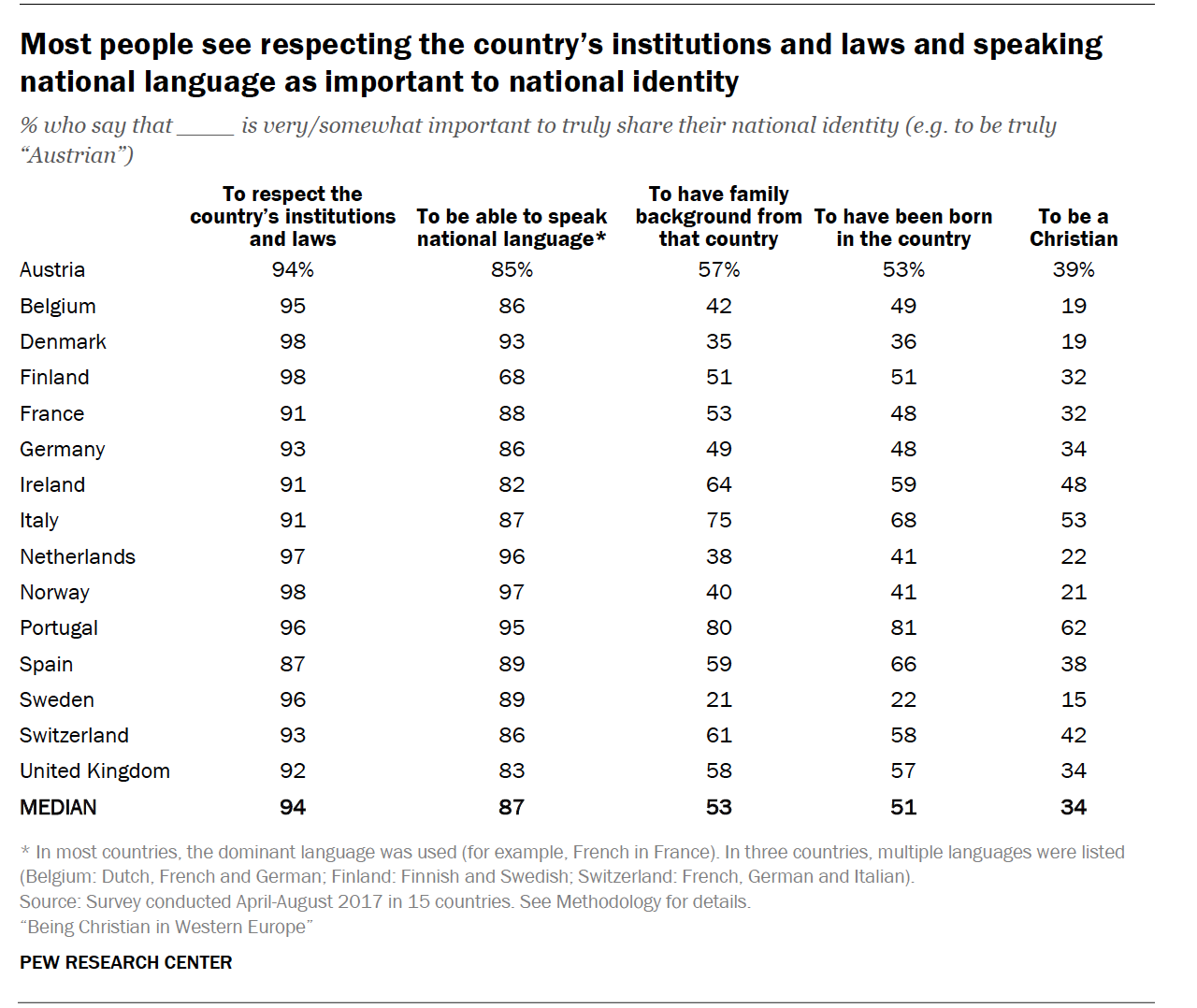

Most Western Europeans emphasize civic elements of their national identity over nativist elements. Overwhelming majorities in every country surveyed say that speaking the national language and respecting their country’s laws are important to truly share the national identity of their country (e.g., it is very important or somewhat important to speak German to be truly German, or to respect the laws of Switzerland to be truly Swiss). By comparison, fewer people take the view that one must have family background in the country, or have been born in the country, to truly share the national identity. Even fewer say one must be Christian to be truly a national of the country (e.g., it is very important or somewhat important to be Christian to be truly French).

Still, roughly half or more in most countries say one must have ancestry in the country, or that one must be born in the country, to truly share the national identity. In Portugal, at least eight-in-ten adults say one must be born in the country (81%) and share its ancestry (80%) to be truly Portuguese.

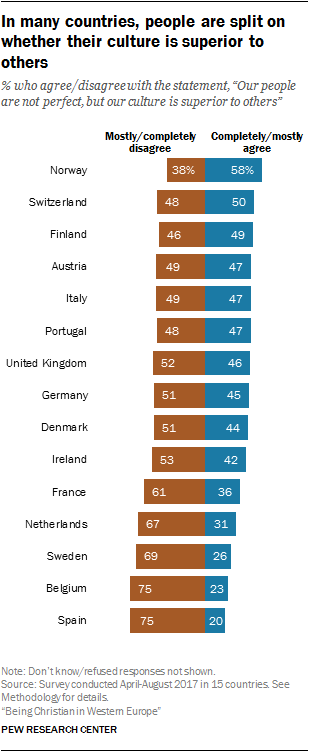

Western Europeans divided over whether their culture is superior to others

Beyond measuring national pride, the survey also sought to measure nationalist sentiment by asking people whether they completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the following statement: “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others.”

Overall, there is no regional consensus on this question. Norway is the only country where a majority of respondents completely or mostly agree that their culture is superior. Conversely, majorities in five nations disagree with this idea, including three-quarters in both Spain and Belgium. Elsewhere, there is a relatively even split between people who agree and disagree with the statement.

Pew Research Center also asked this question in Central and Eastern Europe, where somewhat larger percentages tend to express feelings of cultural superiority, particularly in Greece (89%), Georgia (85%) and Armenia (84%).

Views on immigration

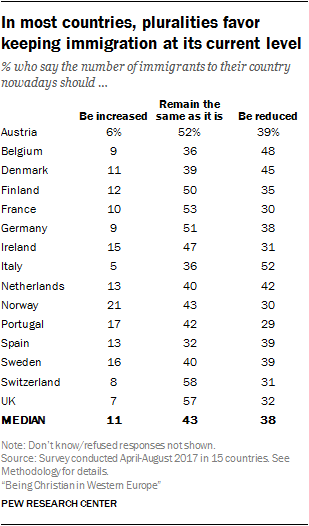

Many Europeans favor the current level of immigration

Western Europeans are much more likely to say that the number of immigrants coming to their country should be reduced than to say immigration levels should be increased (median of 38% vs. 11%).

At the same time, there is a lot of public support for maintaining current levels of immigration. This is the view of a clear majority of adults surveyed in Switzerland (58%) and the UK (57%), as well as roughly half in France (53%), Austria (52%), Germany (51%), Finland (50%) and Ireland (47%).8

Indeed, in most of the 15 countries surveyed, if one adds the people who favor an increase in immigration to those who favor maintaining the current level, then together they outnumber the share of the public that wants to reduce immigration.

A notable exception is Italy, which received an estimated 720,000 migrants between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (the fourth highest total in the region, surpassed only by the UK, Germany and France). More Italians say immigration should be reduced (52%) than say it should be maintained at its current level (36%) or increased (5%). In Belgium, Denmark and Spain, there also is somewhat more public support for reducing immigration than for maintaining current levels. And attitudes on the issue are closely divided in Sweden and the Netherlands.

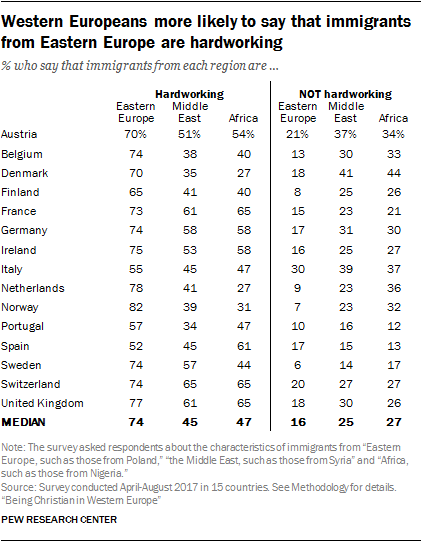

On balance, immigrants from Eastern Europe viewed more positively than those from Middle East or Africa

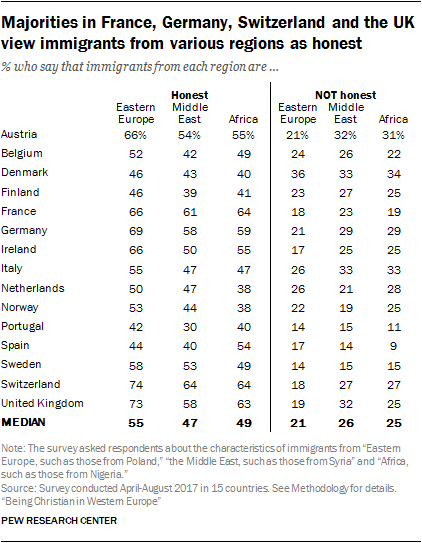

The survey gauged views of immigrants from three different parts of the world by asking respondents whether they associate two positive attributes with each group: working hard and being honest. Across the region, people are more likely to hold these positive views of immigrants from Eastern European countries (like Poland) than those from African countries (like Nigeria) or Middle Eastern countries (like Syria).

Indeed, majorities in nearly every country say Eastern European immigrants in general are hardworking. This includes at least three-quarters in Norway (82%), the Netherlands (78%) and the United Kingdom (77%). By contrast, in fewer than half the countries surveyed do majorities say Middle Eastern or African immigrants are hardworking.

Substantial shares across the region decline to answer these questions. This is especially true in Portugal and Spain, where a quarter of respondents or more say they “don’t know” or decline to answer the questions about immigrants’ work ethic. In most countries, nonresponse is especially common on questions about Middle Eastern and African immigrants.

Still, in several countries, at least three-in-ten say immigrants from outside Europe are not hardworking. About four-in-ten Danish adults take this position about immigrants from the Middle East (41%) and Africa (44%).

Similarly, in most countries surveyed, immigrants from Eastern Europe are more likely than Middle Eastern or African immigrants to be viewed as honest. In Italy, for instance, more than half of the public (55%) says Eastern European immigrants are honest, compared with 47% who say the same about immigrants from both the Middle East and Africa. Fully a third of Italians express the opinion that Middle Eastern and African immigrants are not honest.

Spain is an exception to this pattern; Spanish respondents are more likely to say African immigrants are honest or hardworking compared with those from Eastern Europe or the Middle East.

Again, many respondents decline to answer these questions. In fact, a majority of Portuguese adults (56%) did not offer an answer about whether Middle Eastern immigrants are honest.

Attitudes toward religious minorities

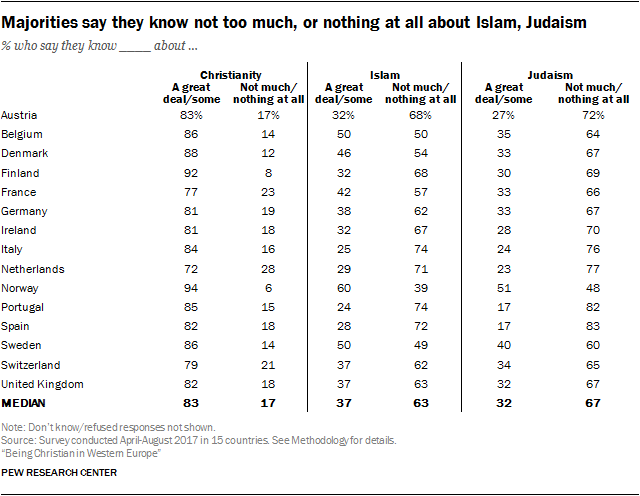

Western Europeans say they know little about Islam, Judaism

Vast majorities in every country surveyed say they know either “some” or a “great deal” about the Christian religion and its practices, including majorities of adults in Norway (62%) and Ireland (56%) who say they know a “great deal” about Christianity.

But in most countries, people tend to say they know “not too much” or “nothing at all” about the Muslim religion and its practices (median of 63%), or the Jewish religion and its practices (median of 67%).

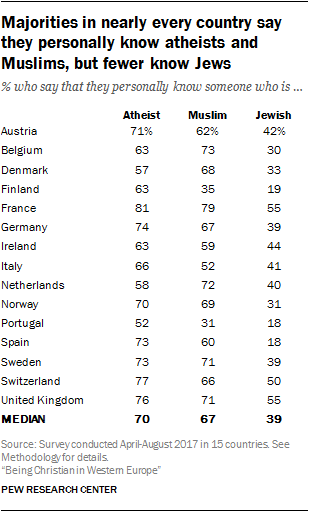

Western Europeans less likely to say they know Jews than Muslims

Although relatively few respondents say they know much about the Islamic religion, far more say they personally know someone who is Muslim. About half or more in every country surveyed say they know a Muslim, with the exceptions of Finland and Portugal.

Throughout the region, fewer Western Europeans say they personally know someone who is Jewish. This finding aligns with the fact that Muslim populations in Europe continue to rapidly rise while Jewish populations in the region have long been falling.

The survey also asked whether respondents personally know an atheist; most people in nearly every country surveyed report that they do.

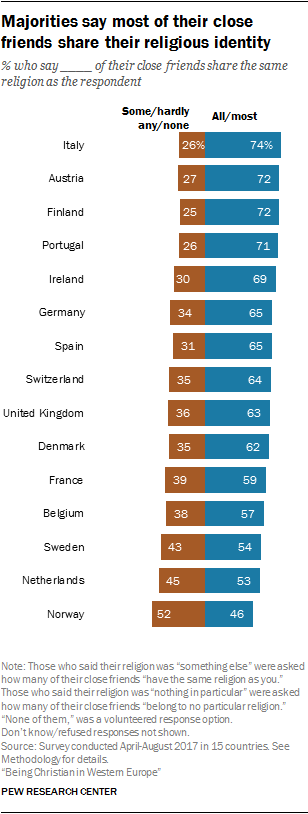

Roughly half of adults in Norway say they have a religiously diverse friendship circle

While many Western Europeans say they know someone who has a different religion, they generally report that their close friendship circles consist largely of people who have the same religious identity that they do.

Majorities in all but three countries say all or most of their close friends share their religion (or, like them, identify as religiously unaffiliated). In Italy, roughly three-in-four people (74%) say their friends generally share their religion. And in Austria, Finland, Portugal and Ireland, where 75% or more of adults identify as Christian, at least two-thirds say all or most of their close friends share their religious identity.

People report more religiously diverse friendship circles in Norway, where about half of respondents (52%) say “some,” “hardly any” or “none” of their close friends share their religious identity.

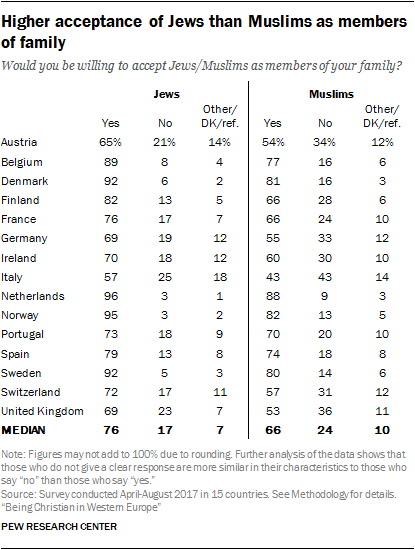

Vast majorities would accept Muslims as neighbors; fewer as family members

To measure openness toward members of minority religious groups, the survey asked respondents a series of hypothetical questions: Would they be willing to accept Jews and Muslims as neighbors, or as

members of their family?

Majorities in every country surveyed say they would be willing to accept Jews as relatives, while overwhelming majorities say that they would be OK with having Jewish neighbors. Majorities in most countries also say they would be willing to accept Muslims as neighbors or family members.

But, on balance, Europeans appear to be somewhat less accepting of Muslims than of Jews. For example, about seven-in-ten British adults (69%) say they would be willing to accept Jews as relatives, while fewer (53%) say this about Muslims. And nearly nine-in-ten respondents in the UK (88%) would accept Jews as neighbors, 10 percentage points higher than the share who say they would accept Muslims as neighbors (78%).

In several countries, significant shares do not express willingness to accept Jews and Muslims in their neighborhoods or families. That is, they either say they would be unwilling to accept these groups in their communities or families, or they decline to answer the question. For example, just under half (46%) of Austrians say they would be unwilling (34%) or do not know whether they would be willing (12%) to accept Muslims as members of their family. Roughly a third of Austrians (35%) say they would be unwilling (21%) or do not know whether they would be willing (14%) to accept Jews in their family.

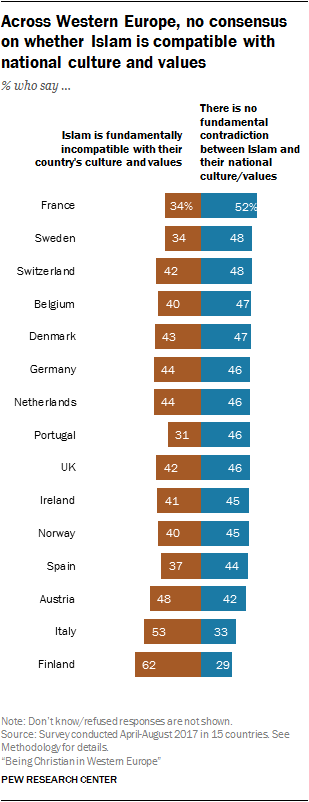

Western Europeans divided over whether Islam is compatible with national values

While most Western Europeans express willingness to accept Muslims as neighbors or family members, they are more divided on whether Islam fits with their national values and culture.

[their country’s]

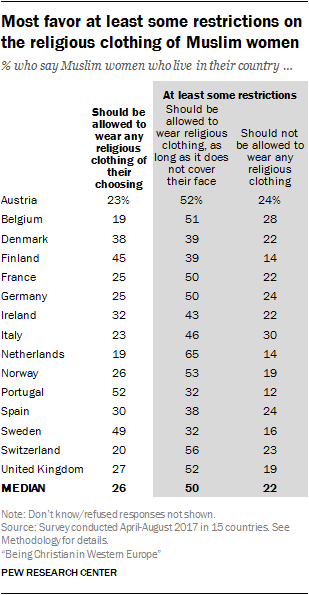

Western Europeans support restrictions on Muslim women’s face coverings

[country]

Most Western Europeans favor restricting the religious clothing worn by Muslim women in their country, especially clothing that covers a woman’s face. Half or more of adults in eight of the 15 countries surveyed favor restricting face coverings, such as niqabs and burqas. And an additional one-in-five or more in most countries favor prohibiting all religious clothing for Muslim women. Combined, majorities in 12 out of 15 countries favor at least some restrictions on Muslim religious dress.

In France, where debates on religious attire in beach towns have been highly publicized and politically charged, 22% of respondents favor restrictions on all religious clothing for Muslim women, while half say that just face coverings should be restricted. On the other hand, roughly half of the public in Portugal (52%) and Sweden (49%) say Muslim women should be allowed to wear whatever religious clothing they want.

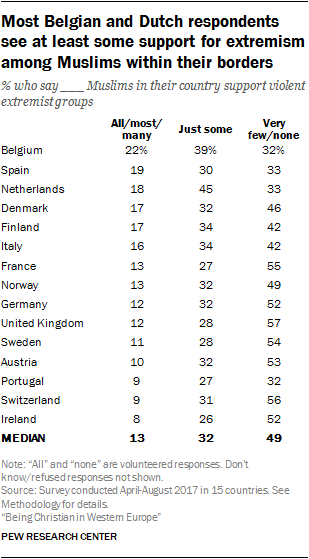

Few say large shares of Muslims in their country support violent extremist groups

In several of the countries surveyed, including the UK, France and Belgium, extremists have carried out attacks in the name of Islam in recent years. However, relatively few Western Europeans think there is widespread support among Muslims in their country for violent extremist groups.

The survey asked respondents to estimate how many Muslims in their country support violent extremist groups: “most,” “many,” “just some” or “very few.” The most common answer is that “very few” or no Muslims support violent extremist groups: A median of 49% of adults across the region choose this option (or volunteer that no Muslims support extremism), including 57% in the UK and 56% in Switzerland. Belgian (32%) and Dutch (33%) respondents are less likely to take this position; most say at least “some” Muslims in their country support violent extremist groups (61% and 63%, respectively).

In some countries, significant shares decline to answer the question. In Portugal, 32% of respondents say that they do not know or refuse to answer the question, as do 18% of respondents in Spain.

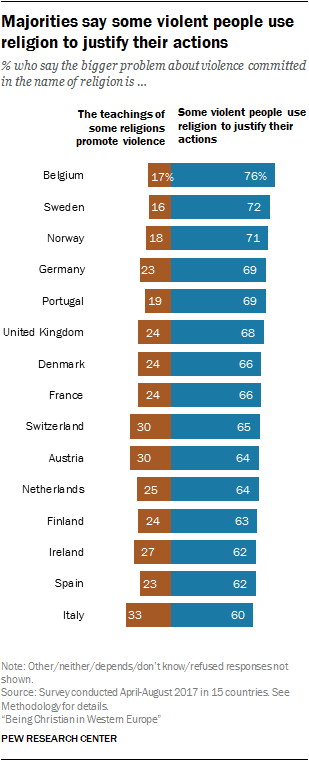

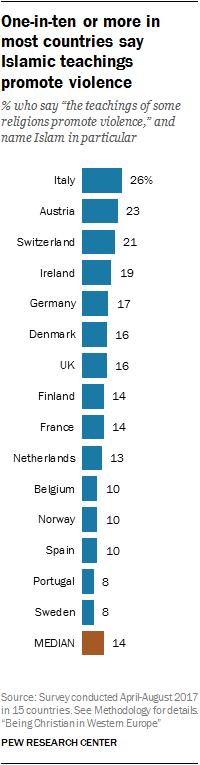

At least one-in-five people in most countries say the teachings of some religions promote violence

The survey was conducted from April to August, 2017, a few months after the Berlin Christmas Market terror attack on Dec. 20, 2016. Interviews were already underway in the UK when the Manchester concert terror attack took place in May 2017.

In light of these and other events, the survey asked respondents to choose which of two statements they consider to be the bigger problem with regard to violence committed in the name of religion: “The teachings of some religions promote violence,” or “Some violent people use religion to justify their actions.” Majorities in every country say the bigger problem is that some violent people use religion to justify their actions.

At the same time, roughly one-in-five or more respondents in most countries say the bigger problem is that the teachings of some religions promote violence. A third of respondents in Italy and three-in-ten in Austria and Switzerland take this position.

Those who said that the teachings of some religions promote violence were asked an open-ended follow-up question: “Which religion or religions in particular have teachings that promote violence?” The most common answer is Islam. Among all respondents, roughly one-in-five or more say this in Italy (26%), Austria (23%), Switzerland (21%) and Ireland (19%). Far fewer Western Europeans mention Christianity or other religions, or say that the teachings of all religions promote violence.

In France, which experienced several terror attacks committed in the name of Islam in the year leading up to the survey, 14% say Islamic teachings promote violence, as do 16% in the UK, where in light of the concert bombing in Manchester, terror threat levels were raised to “critical” while the survey was in the field.

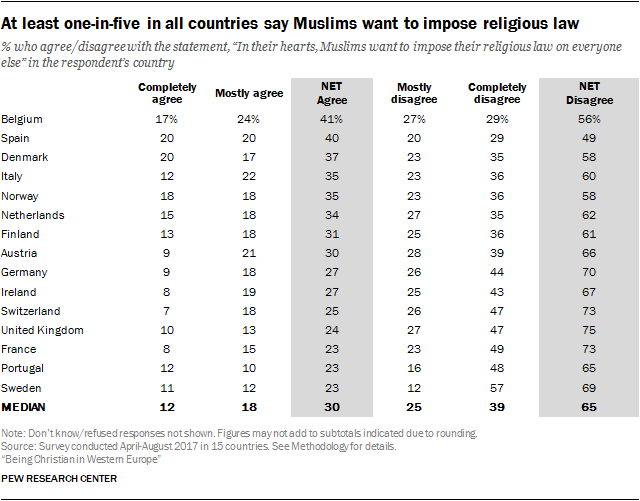

Most disagree with negative statements about Muslims

To further examine Western Europeans’ attitudes toward Islam and Muslims, the survey asked the extent to which people agree or disagree with the following statement: “In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious law on everyone else” in the country. Majorities in almost every Western European country surveyed completely or mostly disagree with this statement.

Still, a median of 30% across the countries surveyed say they either completely or mostly agree with it, including 41% in Belgium and 40% in Spain. One-in-five Spaniards and Danes completely agree that Muslims want to impose religious law on everyone else in their countries.

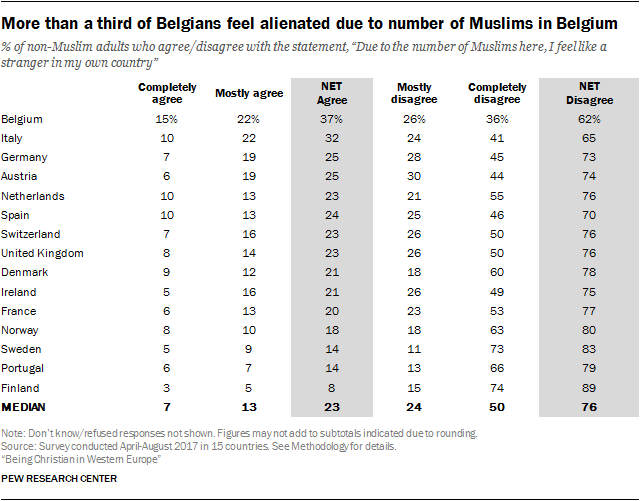

The survey also asked non-Muslim respondents the extent to which they agree or disagree with the following statement: “Due to the number of Muslims here, I feel like a stranger in my own country.” In every country surveyed, large majorities disagree with this statement, including 80% or more in Norway, Sweden and Finland.

In most countries, about one-in-five or more adults agree with the statement, although no more than one-in-ten completely agree. The only exception is Belgium, where 15% completely agree and an additional 22% mostly agree. In Italy, 32% of respondents say they feel like a stranger in their country due to the number of Muslims, and, in Germany, which has received a large number of refugees from predominantly Muslim countries in recent years, 25% express this view.

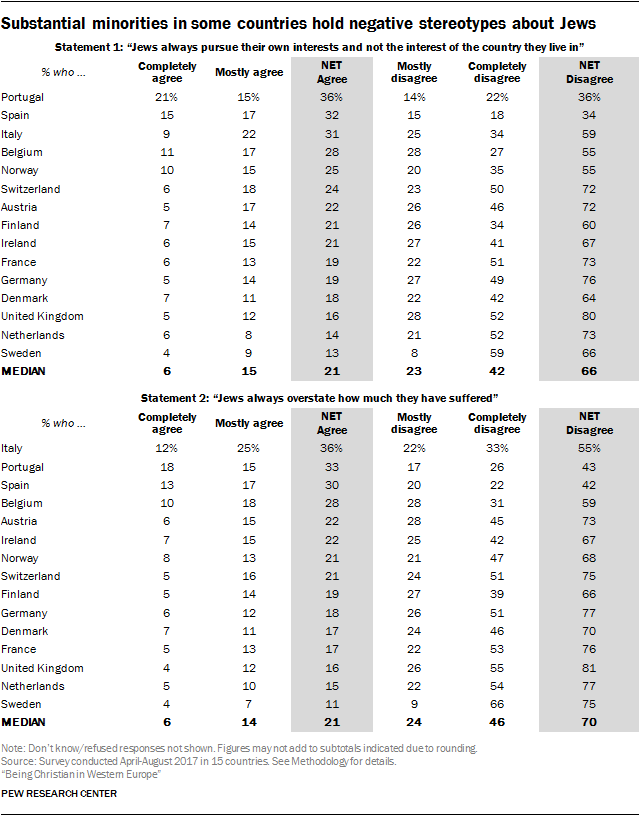

Negative stereotypes about Jews widely rejected

To gauge levels of anti-Jewish sentiment in public opinion in Western Europe, the survey asked respondents whether they completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with two strongly worded negative statements: “Jews always pursue their own interest and not the interest of the country they live in,” and “Jews always overstate how much they have suffered.”

Majorities across the region disagree with both of these statements, including about three-quarters or more in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. Still, about 30% or more in Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Spain completely or mostly agree with each of these statements.

Many respondents decline to answer these questions. In approximately half the countries surveyed, at least one-in-ten people either refuse to say whether they agree or disagree with the statements or say they do not know; these percentages are highest in Spain and Portugal.

Measuring Islamophobia and anti-Semitism

The survey included a few questions in which respondents were asked whether they completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with strongly worded negative statements about Muslims and Jews. These should be interpreted with caution: They were not designed to measure Islamophobia or anti-Semitism in a robust or comprehensive way, but rather to capture some expressed sentiments about these minority groups. Some respondents may harbor negative feelings about Muslims and Jews but not express them to a survey interviewer; others may express hostile feelings in a survey but not have the opportunity or inclination to act in a hostile way. (The survey did not attempt to measure hostile actions or behaviors against religious and ethnic minorities.) Also, the questions about Muslims and Jews were not constructed to parallel each other, so comparisons between the levels of expressed negative sentiment toward the two groups should be made very cautiously, if at all.

Scale of Nationalist, anti-Immigrant, anti-religious Minority sentiment

Overall, attitudes on nationalism, immigration and religious minorities are closely associated with one another. For example, people who express negative views of Muslims also generally favor reducing immigration. And people who voice negative views of Muslims are also more likely to voice negative views of Jews.9

These correlations made it possible for researchers to combine 22 individual questions on these topics into a scale. The higher the score on the scale – on which scores from zero to 10 are possible – the more likely a respondent is to express Nationalist, anti-Immigrant and anti-religious Minority views (NIM). Because the number of questions about each topic varies, each question was weighted so the three topics covered have equal impacts on the scale.10

The NIM scale illuminates country-level variations. Swedes are the least likely to express nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-minority views (8% score higher than 5). Italians, meanwhile, score relatively high on the scale: Nearly four-in-ten (38%) score above 5, a larger share than in any other country surveyed. Median scores in the 13 other countries fall in between Sweden’s median (1.2) and Italy’s (4.1).

What goes into the Nationalist, anti-Immigrant and anti-Minority (NIM) scale

The following questions were combined into a scale such that questions on each of the three topics (nationalism, immigration and religious minorities) contributed equally to the scale. Scores increase by the amount noted below if a respondent says …

Nationalism (each worth 1.11 points)

- It is very/somewhat important to have been born in [COUNTRY] to be truly [NATIONALITY] (e.g., to have been born in France to be truly French).

- It is very/somewhat important to have [NATIONALITY] family background to be truly [NATIONALITY] (e.g., to have French family background to be truly French).

- I completely/mostly agree that, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others.”

Immigration (each worth 0.48 points)

- The number of immigrants to [COUNTRY] should be reduced.

- Immigrants from Eastern Europe, such as those from Poland, are not hardworking

- Immigrants from the Middle East, such as those from Syria, are not hardworking

- Immigrants from Africa, such as those from Nigeria, are not hardworking

- Immigrants from Eastern Europe, such as those from Poland, are not honest

- Immigrants from the Middle East, such as those from Syria, are not honest

- Immigrants from Africa, such as those from Nigeria, are not honest

Religious minorities (each worth 0.28 points)

- I am not willing, or don’t know (or declined to answer) if I’m willing, to accept Muslims as neighbors.

- I am not willing, or don’t know (or declined to answer) if I’m willing, to accept Muslims as family members.

- I am not willing, or don’t know (or declined to answer) if I’m willing, to accept Jews as neighbors.

- I am not willing, or don’t know (or declined to answer) if I’m willing, to accept Jews as family members.

- I completely/mostly agree that, “In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious law on everyone else in [COUNTRY].”

- I completely/mostly agree that, “Due to the number of Muslims here, I feel like a stranger in my own country.”

- I completely/mostly agree that, “Jews always overstate how much they have suffered.”

- I completely/mostly agree that, “Jews always pursue their own interests and not the interest of the country they live in.”

- Islam has teachings that promote violence.

- All/most/many Muslims in the country support violent extremist groups

- Muslim women who live in the country should not be allowed to wear any religious clothing.

- Islam is fundamentally incompatible with the country’s culture and values.

The scale provides an opportunity to analyze which attributes are most closely associated with a person’s likelihood of expressing nationalist opinions and negative views of religious minorities and immigrants. Overall, Christians (both church-attending and non-practicing) are more likely than religiously unaffiliated people to score higher than 5 on the NIM scale. For example, in the UK, 27% of churchgoing Christians and 24% of non-practicing Christians score higher than 5 on the NIM scale, compared with 15% of “nones.”

But many factors could be correlated with holding nationalist, anti-immigration and anti-minority views. Controlling for a variety of variables – such as age, gender, education, political ideology, personal economic situation, religious affiliation, religious observance, and more – researchers conducted statistical analysis of the survey data to determine which characteristics stand out above the others.

Independent of other factors, Western Europeans who identify as Christian (whether churchgoing or not) score higher on the NIM scale than those who have no religious affiliation. Put more simply: Christian identity, on its own, is associated with higher levels of nationalism and negative views of religious minorities and immigrants.11

This is not to say that most Christians in Europe oppose immigration or want to keep Muslims and Jews out of their neighborhoods. In all 15 countries surveyed, fewer than half of all Christians score higher than 5 on the scale. The results also do not imply that Christian theology or religious teachings necessarily lead to anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim or anti-Jewish positions; on the contrary, many churches have been active in resettling refugees from the Middle East and elsewhere. Theoretically, the causal connection could go in either direction (or in both directions): It could be that holding anti-immigrant positions may lead a person to embrace Europe’s historically dominant religious identity, rather than that identifying with Europe’s historically dominant religious group leads a person to take anti-minority positions. The survey data show a statistical correlation – not a clear relationship of cause and effect.

Moreover, religious identity is far from the only characteristic associated with where respondents stand on these questions. The analysis also finds that personal familiarity with Muslims or Jews is associated with lower NIM scores. That is, people who say they personally know a Muslim tend to have lower scores on the scale (i.e., to be more accepting of immigrants and minorities, and to be less nationalistic). To a lesser extent, the same pattern holds for those who personally know a Jewish person, although significantly more people in Europe today say they are personally acquainted with Muslims than with Jews.

Political ideology also is tied very closely to NIM scores.12 People who describe their political views as being more toward the right wing in their country are much more likely to score high on the scale, compared with those who classify themselves as left-leaning. Education, too, is a strong factor: Adults with college degrees are considerably more likely than those with less education to score low on the NIM scale.

The relationship between age and NIM scores is weaker. While younger people tend to score lower on the NIM, statistical analysis suggests that this has to do less with their age and more with other, related factors such as ideology, religion and familiarity with Muslims. For example, younger people are considerably more likely than older people to say they personally know a Muslim. They are also more likely than older adults to say they are religiously unaffiliated. Both factors are closely associated with lower NIM scores.

Many intangible factors can influence how respondents choose to answer questions on sensitive topics like nationalism, immigration and the place of minorities in European society, including the general proclivity of people to frame their views in a manner than is socially acceptable. Nonetheless, the survey reveals several measurable attributes that are correlated with these views. All in all, Christian affiliation and right-wing political ideology are closely associated with higher levels of nationalist, anti-immigration and anti-minority views, while college education and personal familiarity with Muslims are associated with lower levels of nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-minority sentiment.

Measuring religious commitment

In many places in this report, religious commitment is measured primarily by attendance at religious services: Christians who attend church at least monthly are categorized as churchgoing Christians, while those who attend no more than a few times a year are categorized as non-practicing Christians. Many scholars consider attendance at religious services a standard measure of religious observance, especially for Christians. But church attendance is not the only way to measure Christian religious commitment. An alternative approach, also used in this report, combines four separate measures of religious commitment into an index: how important a person considers religion in their lives, how often they attend religious services, how often they pray and whether they believe in God with absolute certainty. Christian respondents are classified as high, medium or low in their religious commitment based on their scores on the index.

If one replaces “churchgoing Christians” and “non-practicing Christians” with this more complex scale (high, medium and low levels of religious commitment), the NIM regression models continue to find significant differences between Christians (at all levels of religious commitment) and religiously unaffiliated adults in the region. For the results of this regression model, see Appendix A.