As the coronavirus pandemic continues apace, people in the United States and Germany express different views about international relations and globalization, according to surveys conducted in both nations in April.

Compared with previous years, Germans are increasingly negative about their relationship with the U.S., even as both Americans and Germans expect international relations to change after the pandemic. Meanwhile, Germans are more comfortable than Americans with globalization and its effects.

The surveys are the latest in a series of polls conducted under a partnership between Pew Research Center in the U.S. and Körber-Stiftung in Germany. Below are five takeaways from the new surveys.

In 2017, Pew Research Center and Körber-Stiftung began collaborating on joint public opinion surveys to gauge the state of relations between the United States and Germany. The questions were developed together, and each organization fielded a survey within its own country starting that year. Some of the questions have been repeated annually to allow both organizations to track attitudes over time. Topics include relations with other countries, defense spending and military deployments, and general foreign policy attitudes. This year, questions about the coronavirus pandemic were also asked.

The results have been published in both countries, and the previous reports from Pew Research Center can be found here for 2019, 2018 and 2017.

The Körber-Stiftung findings are contained within their larger “Berlin Pulse” report and can be found here for 2019/2020 and 2018.

The 2020 findings come from a Pew Research Center survey conducted by SSRS in the U.S. from April 21-26 among 1,008 respondents and a Körber-Stiftung survey conducted by Kantar in Germany from April 3-9 among 1,057 respondents.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with the responses, and its U.S. survey methodology.

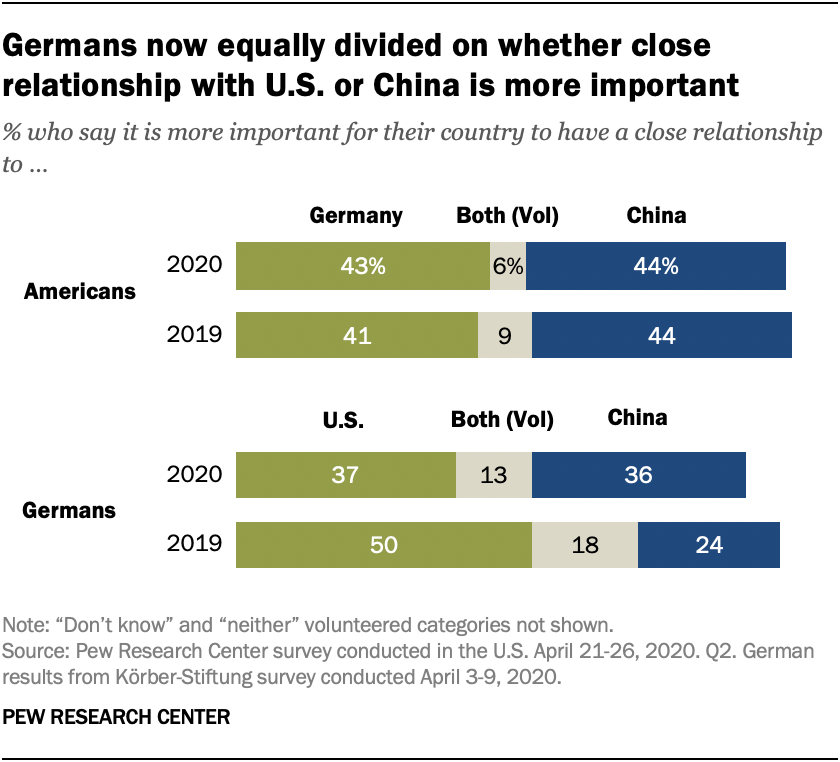

1In a shift, Germans now see their country’s relationship with China as equally important as their relationship with the U.S. In 2019, about twice as many Germans prioritized their country’s relationship with the U.S. over China (50% vs. 24%). Since then, however, the share of Germans who say it is more important for their country to have a close relationship with the U.S. has fallen 13 percentage points, while the share who prioritize a close relationship with China has gone up by 12 points. Today, 37% of Germans say they prioritize their country’s relationship with the U.S. while a nearly equivalent share (36%) prioritize relations with China.

1In a shift, Germans now see their country’s relationship with China as equally important as their relationship with the U.S. In 2019, about twice as many Germans prioritized their country’s relationship with the U.S. over China (50% vs. 24%). Since then, however, the share of Germans who say it is more important for their country to have a close relationship with the U.S. has fallen 13 percentage points, while the share who prioritize a close relationship with China has gone up by 12 points. Today, 37% of Germans say they prioritize their country’s relationship with the U.S. while a nearly equivalent share (36%) prioritize relations with China.

There has been virtually no change among Americans. Just as in 2019, a little over four-in-ten Americans say it is more important to have a close relationship with Germany (43%), while nearly the same share (44%) prioritize relations with China.

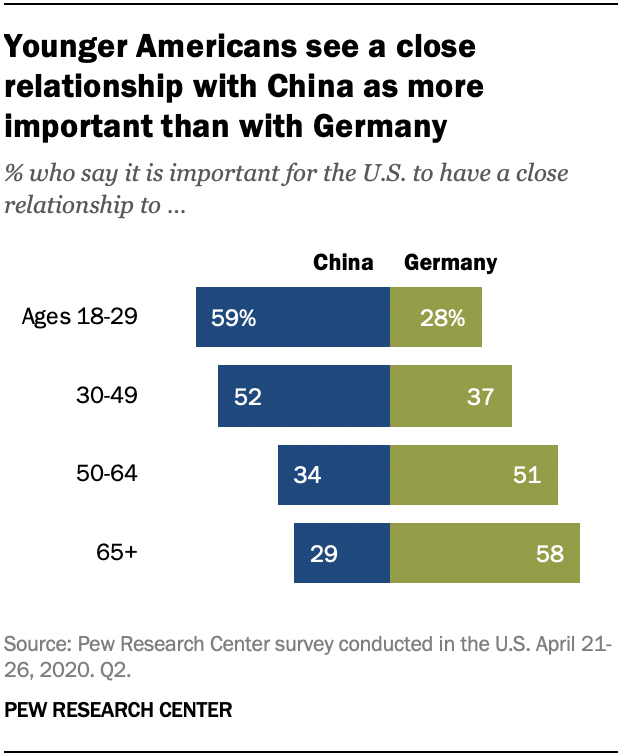

Younger Americans see their country’s relationship with China as more important than the one with Germany. About six-in-ten Americans ages 18 to 29 favor a closer relationship with China. By contrast, 58% of Americans ages 65 and older prefer a close relationship with Germany.

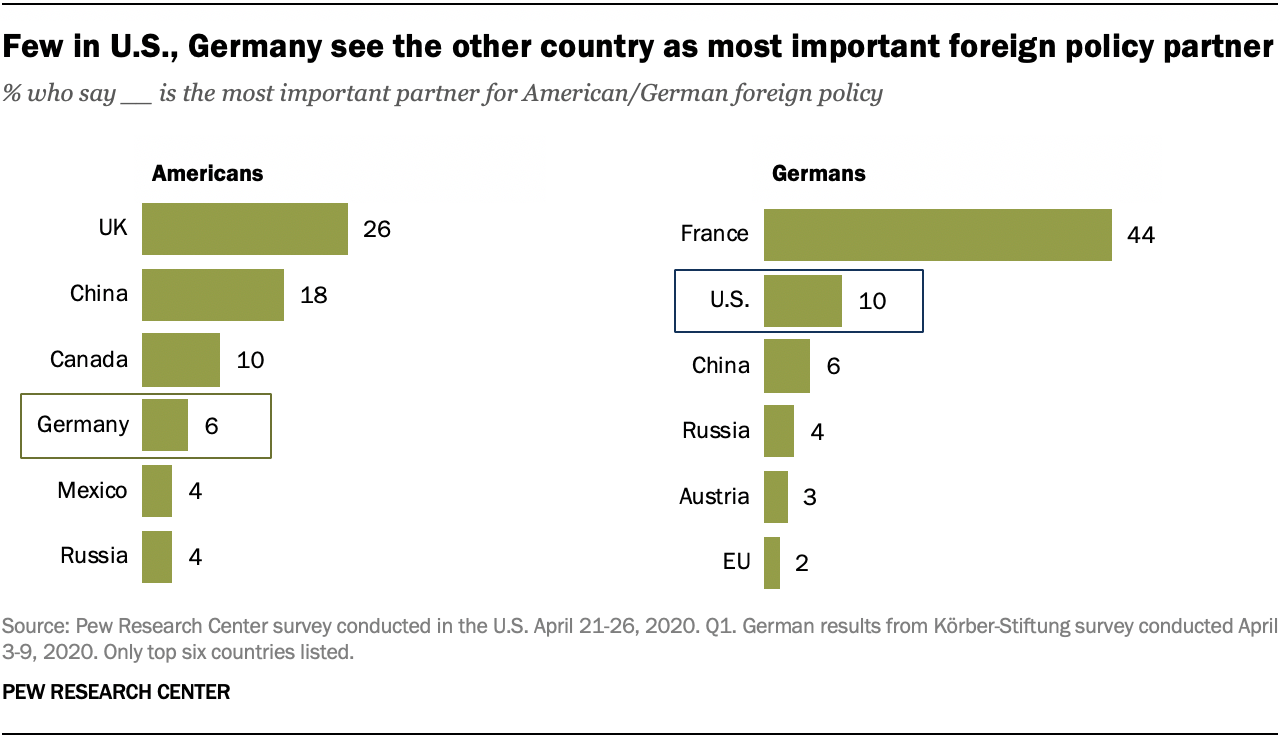

2Germans see France as their country’s top foreign policy partner, while Americans name the United Kingdom. Germans and Americans do not view the other country as their own nation’s principal foreign policy partner. More than four-in-ten Germans (44%) name France as the most important foreign policy partner for their country; 10% of Germans name the U.S. Meanwhile, roughly a quarter of Americans (26%) cite the UK as their country’s most important partner, while Germany is a distant fourth, cited by 6% of U.S. adults, similar to the share (4%) expressed in 2019. Last year, around two-in-ten Germans (19%) saw the U.S. as their country’s top partner.

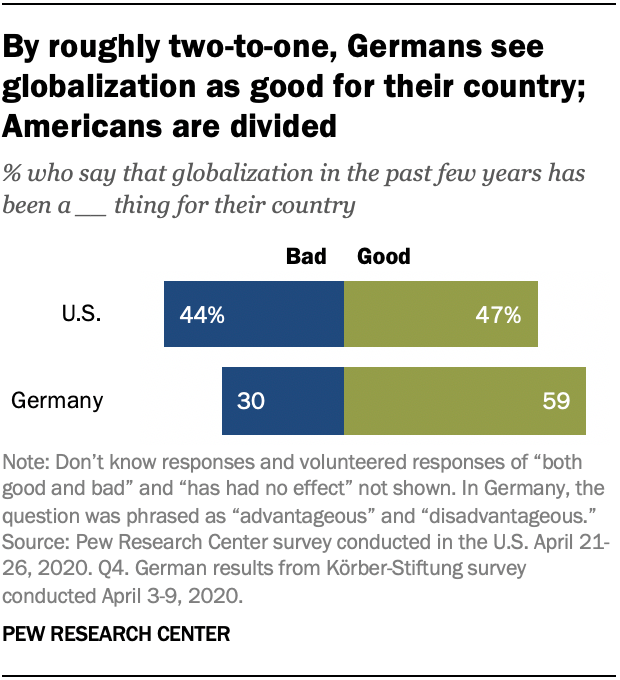

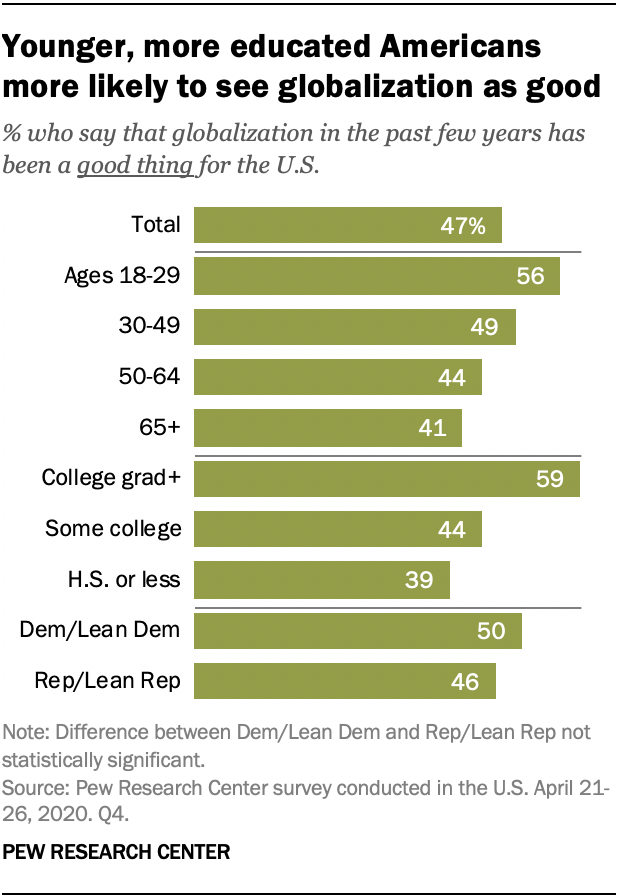

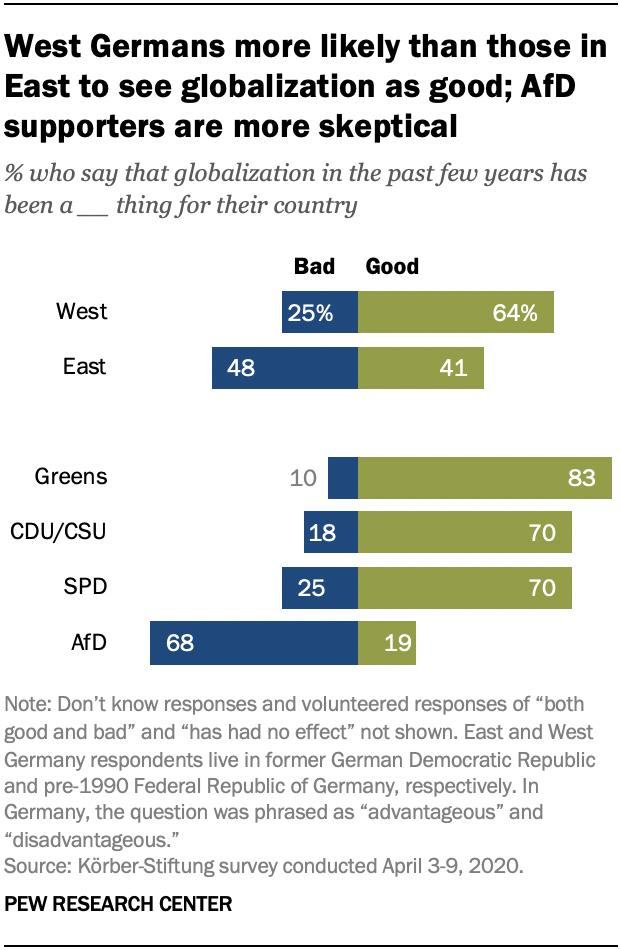

3Germans are more positive about globalization than Americans, but there are divisions within each country. When asked whether globalization in the past few years has been a good thing or bad thing for their country, Americans are about evenly divided (47% vs. 44%). By comparison, nearly six-in-ten Germans (59%) see globalization as advantageous to their country, while only three-in-ten say it has been a bad thing. (The surveys did not define globalization.)

3Germans are more positive about globalization than Americans, but there are divisions within each country. When asked whether globalization in the past few years has been a good thing or bad thing for their country, Americans are about evenly divided (47% vs. 44%). By comparison, nearly six-in-ten Germans (59%) see globalization as advantageous to their country, while only three-in-ten say it has been a bad thing. (The surveys did not define globalization.)

In the U.S., views of globalization differ significantly by age and education. Americans ages 18 to 29 are 15 percentage points more likely than those 65 and older to say globalization has been a good thing for their country (56% vs. 41%). And Americans with a four-year college degree or more education are 20 points more likely than those with a high school education or less to say this (59% vs. 39%).

Similar shares of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (50%) and Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (46%) say globalization is good for the U.S.

In Germany, views on globalization differ by geography and party. Those who live in the former West Germany are 23 points more likely than those in the former East to say globalization has been a good thing for their country (64% vs. 41%).

In Germany, views on globalization differ by geography and party. Those who live in the former West Germany are 23 points more likely than those in the former East to say globalization has been a good thing for their country (64% vs. 41%).

Germans who support the right-wing populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD) are overwhelmingly opposed to globalization. Only 19% of AfD supporters say globalization has been a good thing for Germany, compared with 83% of those who support the Greens and 70% of supporters of the CDU/CSU or SPD.

On a separate question about globalization’s effects on the personal lives of Americans and Germans, pluralities in each country say that this benefits them on a personal level About half of Germans (52%) say globalization is good for them personally, and 49% of Americans agree.

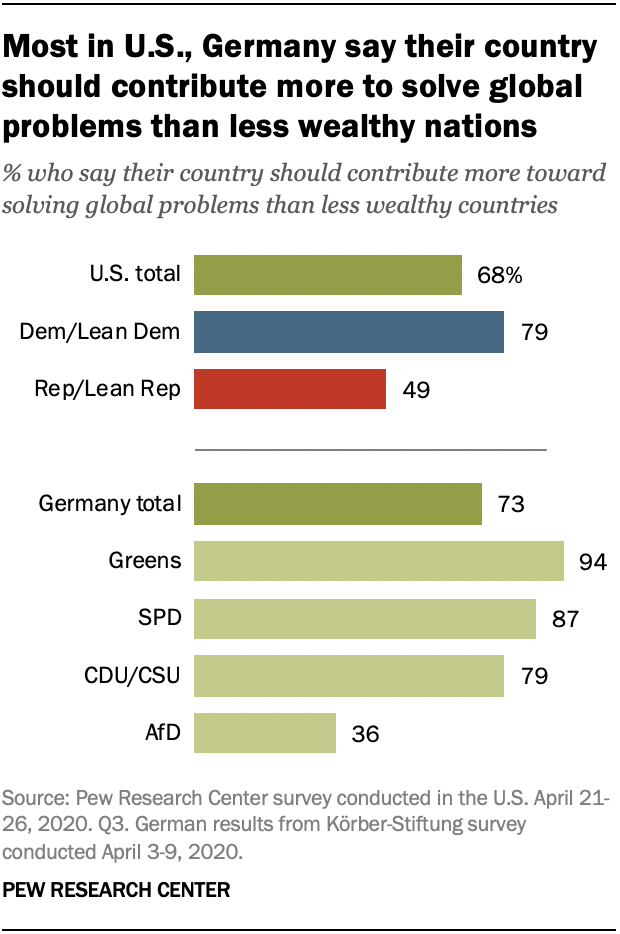

4Americans and Germans overwhelmingly agree that their country should do more than less wealthy countries to help solve global problems. Two-thirds or more of both Americans (68%) and Germans (73%) say their country should do more to help solve global problems than less wealthy countries. Only about a quarter of Germans (24%) and three-in-ten Americans disagree with this sentiment.

4Americans and Germans overwhelmingly agree that their country should do more than less wealthy countries to help solve global problems. Two-thirds or more of both Americans (68%) and Germans (73%) say their country should do more to help solve global problems than less wealthy countries. Only about a quarter of Germans (24%) and three-in-ten Americans disagree with this sentiment.

In the U.S., there are sizable partisan differences: 79% of Democrats say the U.S. should contribute more to solving global problems than less wealthy nations, while 49% of Republicans agree.

In Germany, supporters of the Greens are most enthusiastic about helping solve global problems. But supporters of the SPD and CDU/CSU are also in favor of Germany contributing more than less wealthy nations. AfD supporters are strongly opposed to Germany doing more to solve world problems than less wealthy countries; just 36% support this.

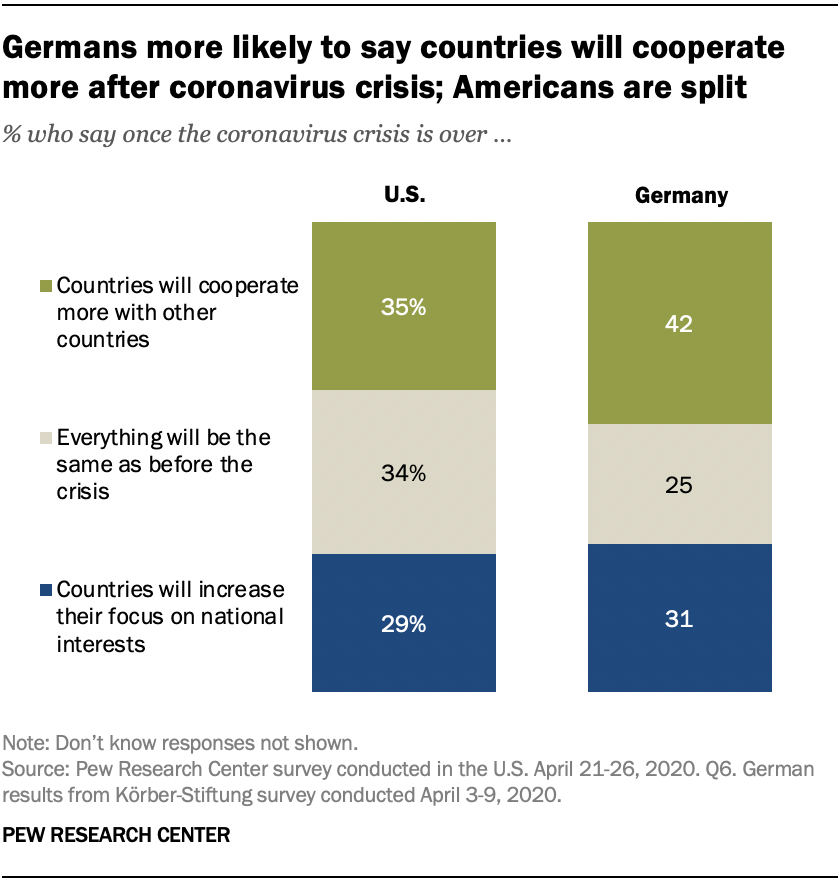

5Germans and Americans agree foreign relations will change once the coronavirus crisis is over, but they differ somewhat over how things will change. Around four-in-ten Germans (42%) say countries will cooperate more with each other after the crisis, while a smaller share (31%) say countries will increase their focus on national interests. Americans are more divided on this question: 35% say countries will cooperate more, while 29% say nations will focus more on their own interests. In both countries, only around a third or fewer say everything will be the same as before the coronavirus crisis.

5Germans and Americans agree foreign relations will change once the coronavirus crisis is over, but they differ somewhat over how things will change. Around four-in-ten Germans (42%) say countries will cooperate more with each other after the crisis, while a smaller share (31%) say countries will increase their focus on national interests. Americans are more divided on this question: 35% say countries will cooperate more, while 29% say nations will focus more on their own interests. In both countries, only around a third or fewer say everything will be the same as before the coronavirus crisis.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with the responses, its U.S. survey methodology, and the full dataset.