The focus of this report is the creation of a new typology of Americans’ public engagement with public libraries, which sheds light on broader issues around the relationship between technology, libraries, and information resources in the United States. It serves as a capstone to the three years of research the Pew Research Center has produced on the topic of public libraries’ changing role in Americans’ lives and communities.

Briefly put, a typology is a statistical analysis that clusters individuals into groups based on certain attributes; in this case, those are people’s usage of, views toward, and access to libraries. While Pew Research has reported in extensive detail on the ways different groups use public libraries—including insights about differences by gender, race/ethnicity, age, income and community type—this typology enriches that picture considerably by moving beyond familiar groups and fitting demographics into contexts that matter to the library community.3 By creating groups based on their connection to libraries rather than their gender, age, or socio-economic attributes, this report allows portraiture that is especially relevant to library patrons, library staff members, and the people whose funding decisions impact the future of public libraries in the United States.

Among the broad themes and major findings in this report:

- Public library users and proponents are not a niche group: 30% of Americans ages 16 and older are highly engaged with public libraries, and an additional 39% fall into medium engagement categories.

- Americans’ library habits do not exist in a vacuum: Americans’ connection—or lack of connection—with public libraries is part of their broader information and social landscape. As a rule, people who have extensive economic, social, technological, and cultural resources are also more likely to use and value libraries as part of those networks. Many of those who are less engaged with public libraries tend to have lower levels of technology use, fewer ties to their neighbors, lower feelings of personal efficacy, and less engagement with other cultural activities.

- Life stage and special circumstances are linked to increased library use and higher engagement with information: Deeper connections with public libraries are often associated with key life moments such as having a child, seeking a job, being a student, and going through a situation in which research and data can help inform a decision. Similarly, quieter times of life, such as retirement, or less momentous periods, such as when people’s jobs are stable, might prompt less frequent information searches and library visits.

The spectrum of public library engagement in America

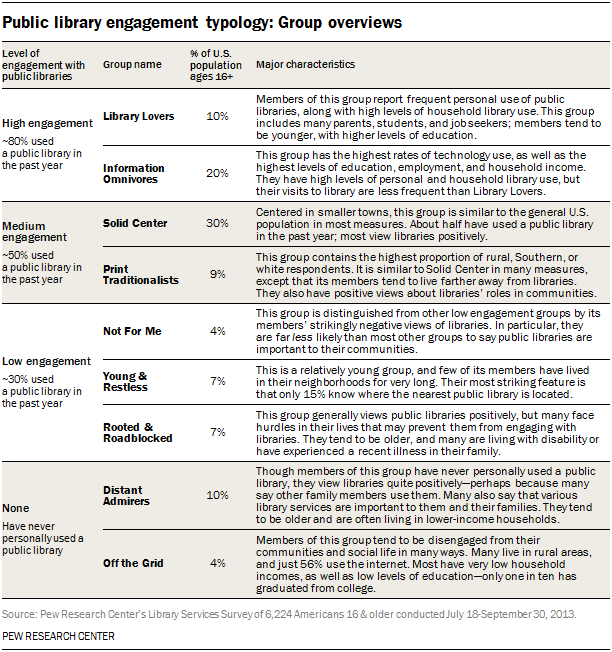

This report describes nine groups of Americans that reflect different patterns of public library engagement. Respondents were sorted into groups based on a cluster analysis of factors such as: the importance of public libraries in their lives; how they use libraries; and how they view the role of libraries in communities. (For more information about how the typology was created, see the overview in About This Typology; further details are available in the Methods section at the end of the report.) For each group, we describe not only their library habits and views, but also their larger information and technology habits and to what extent various demographic groups are represented.

The typology examines four broad levels of library engagement. These levels are further broken into a total of nine individual groups:

High engagement

- Library Lovers

- Information Omnivores

Medium engagement

- Solid Center

- Print Traditionalists

Low engagement:

- Not for Me

- Young and Restless

- Rooted and Roadblocked

Non-engagement (have never personally used a public library):

- Distant Admirers

- Off the Grid

The high, medium, and low engagement groups include Americans who have ever used a public library at some point in their lives, while the non-engagement groups include Americans who have never personally used a public library (either in person or online).

The members of the two high engagement groups, Library Lovers and Information Omnivores, include people who value and utilize public libraries most heavily—those who say that libraries play a major role in their own lives and in the lives of their families, who think libraries improve their communities, who are avid readers and think libraries play an essential role in encouraging literacy and a love of reading. Members of these high engagement groups also tend to be active in other parts of their communities. They tend to know their neighbors, they are more likely to visit museums and attend sporting events, and they are more likely to socialize with families and friends.

On the other hand, those who are less engaged with public libraries are often less engaged in their communities overall. Particularly for the low engagement groups Not for Me and Rooted and Roadblocked, along with the non-engagement groups Distant Admirers and Off the Grid, lower rates of library use and lack of familiarity with libraries seem to coincide with lower patterns of social and civic engagement in other areas of their lives. Members of low and non-engagement groups are often less likely to participate in similar community activities, such as visiting museums or patronizing bookstores, and more likely to report having difficulty using technology; they also tend to be less comfortable navigating various types of information, such as finding material about government services and benefits.

Group portraits

High engagement groups

Library Lovers (10% of the population)

- Overview: Library Lovers have strikingly positive views of public libraries compared with other groups, and with the U.S. population as a whole; they use libraries and library websites more than any other group, and believe libraries are essential at the personal as well as the community level.

- Who they are: Demographically, this group’s members are disproportionately younger than the general population. A relatively large proportion of this group are women (62%), and this group has the highest proportion of parents (40%) of any group. They tend to have higher levels of education and somewhat higher household incomes than many other groups, but a notable share of them are in economically challenging circumstances: 23% have recently lost their jobs or seen a significant loss of income; 25% are currently looking for a job; 17% are students. Politically, they are more likely to be liberal and Democratic than the general population.

- Lifestyle: This group includes many heavy book readers (66% read a book daily). Though they are heavy library users and generally prefer to borrow books instead of purchasing them, they are also have the highest proportion of regular bookstore visitors (57%) than any other group. More than other groups, they like to learn new things and enjoy tracking down information. They are also active socially and engaged with community events, and rate their communities highly. They are also heavy internet users, and are particularly engaged with mobile: 72% go online via mobile devices.

- Relationship with libraries: They are the leading group in use of and affection for libraries: 87% visited the library in the last 12 months, most of them visiting weekly. And 75% say that the local library closed it would have a major impact on them personally, significantly more than any other group.

Information Omnivores (20% of the population)

- Overview: Information Omnivores are more likely to seek and use information than other groups, are more likely to have and use technology; at the same time, they are strong users of public libraries, and think libraries have a vital role in their communities. However, they are not quite as active in their library use as Library Lovers, or nearly as likely to say the loss of the local library would have a major impact on them and their family.

- Who they are: Information Omnivores are the highest ranking group in socio-economic terms: 35% live in households earning $75,000 or more, and they have one of the highest employment rates and are relatively well educated. Like Library Lovers, this group includes relatively high proportions of women (57%) and parents (40%). With a median age of 40, they are a bit younger than the U.S. population as a whole. It is also one of the more urban groups. Politically they are more likely to be Democratic and liberal compared with the general U.S. population.

- Lifestyle: As a group, Information Omnivores are the most intense users of technology: among internet users, 90% go online every day, and 81% use social media. Almost half (46%) have a tablet computer, the highest proportion of any group, and 68% own a smartphone. They rank just below Library Lovers in their consumption of books—they read an average of 17 books in the previous 12 months—and are more likely to buy their books than borrow them.

- Relationship with libraries: They appreciate public libraries a lot, especially as community resource: 85% strongly agree that libraries are important because they promote literacy, and 78% strongly agree that libraries improve the quality of life in their communities. Information Omnivores use libraries more than any other group except Library Lovers, though they use the library less often than that group and would not take the loss of their library at such a profound personal level. However, 77% say the loss of the library would be a major blow to their community.

Medium engagement groups

Solid Center (30% of the population)

- Overview: The Solid Center is the largest group in our typology, and its members generally track with the general U.S. population—in their demographic proportions, in their technology use, in their patronage of libraries, and in their approach to information, and their views about the importance and role of libraries. They mostly view libraries positively, but a third (32%) report their library use has declined in the past five years.

- Who they are: Compared with national benchmarks, this group includes a slightly higher proportion of men (51%) than the general U.S. population; its median age is 47. Its members are more likely than some other groups to live in small towns and cities, and half have lived in their communities for longer than 10 years. Those in the Solid Center are significantly less likely than high engagement groups to include parents with minor children living at home (28%).

- Lifestyle: They rank high among the groups in appreciating their communities: 84% would describe their communities as “good” or “excellent.” In their attendance of various community activities, those in the Solid Center are not quite as involved as the high engagement groups, but they are fairly active: 34% got to sporting events regularly, 28% regularly go to bookstores, 27% regularly go to concerts, plays, or dance performances, and 26% regularly go to museums or art galleries. They read books at the same frequency as the U.S. populations.

- Relationship with libraries: Some 58% have library cards, and 43% visited the library in the past 12 months; their visits are not as frequent as high engagement groups, with most saying they visit the library monthly or less often. They are one of the least likely groups to use library websites: only 5% used a library website in the past year, and only 26% have ever used one. Most members of the Solid Center rate libraries highly as community resources: 67% say that libraries improve the quality of life in a community and 61% say their library’s closing would have a major impact on their community.

Print Traditionalists (9% of the population)

- Overview: Members of this group read an average of 13 books in the past 12 months, and tend to value the traditional services libraries perform. They are also in one of the higher ranking groups in expressing appreciation for the role of libraries in communities. They are notable for the distance most of them would need to travel to visit a library—only one in ten (11%) say the nearest public library is five miles away or less.

- Who they are: The Print Traditionalist group has the highest proportions of rural (61%), white (75%), and Southern (50%) respondents. They also have a higher proportion of women (57%) than the general population. Print Traditionalists are less likely than some other groups to have graduated college, as about half of adults in this groups ended their education with a high school diploma. Their median age is 46, and their political views lean conservative.

- Lifestyle: Print Traditionalists are more likely to have lived in their neighborhoods longer than many other groups, and are especially likely to say they know the names of all or most of their neighbors; they also tend to have positive feelings about where they live, and are generally quite social: 81% say they socialize with friends or family every day or almost every day. They have access to technology at roughly the same rates as the general population, but they use technology less than other higher engagement groups.

- Relationship with libraries: Print Traditionalists stand out in their positive views about the role of libraries in communities: 80% say libraries are important because they promote literacy; 75% say libraries play an important role because they give everyone a chance to succeed; and 73% say libraries improve the quality of life in the community. They also have one of the highest proportion of members reporting that if the local library closed it would have a major impact on the community. Some 48% say they visited the library in the last 12 months, and most say their own library use has not changed in the past five years.

Low engagement groups

Not For Me (4% of the population)

- Overview: As a low engagement group, Not for Me is made up of respondents who have used public libraries at some point in their lives, though few have done so recently. Their portrait suggests a level of alienation—34% believe people like them can have no impact in making their communities better—and are somewhat less engaged socially and from other community activities: 45% do not regularly do any of the community activities we asked about, such as attending sports events, museums, or going to bookstores. Finally, they have strikingly less positive about role of libraries in communities, even when compared with other low engagement groups, and more than half (57%) say they know “not much” or “nothing at all” about the library services in their area.

- Who they are: The Not for Me group includes a somewhat higher proportion of men (56%), and its respondents are more likely to live in small town or rural areas. Its members are more likely to have lower levels of educational attainment, with just 18% having graduated from college. Members of this group are also somewhat less likely to be married (41%), and are a little less likely to be parents (26%) than the general population. Just 39% are employed full-time, and almost a quarter (23%) are retired.

- Lifestyle: Few in this group are heavy book readers: 31% read did not read any books last year, and as a group they read a median of 3 books in that time. They also have somewhat lower levels of internet adoption and use, and are more likely than other groups to report having difficulty getting information about such things as politics and current events, community activities, health information, and career opportunities

- Relationship with libraries: Some 40% have library cards, similar to other low engagement groups; 31% visited the library in the past year, and just 12% used a library website. Relative to other groups, they are more likely to say they find libraries hard to navigate and are less likely to say they rely on individual library services. Fully 64% say library closings would have no impact on them or their family, and just 20% strongly agree that having a public library improves the quality of life in a community. Finally, 70% say that people do not need public libraries as much as they used to because they can find most information on their own.

Young and Restless (7% of the population)

- Overview: Though relatively small, this group contains a higher proportion of young people than most other groups, most of them relatively new to their communities. This may be why only 15% of its members say they even know where the local library is, fewer than any other group in the typology. Only a third have a library card or visited a library in the past year, though unlike the Not for Me group, most Young and Restless respondents have positive views of libraries overall.

- Who they are: We call them “restless” because many are new to their communities: A third of them have lived in their communities less than a year. Their median age is 33, making them the youngest group overall, and 53% are male. They include a high proportion of urban dwellers, and are more often found in the South than members of the U.S. population as a whole . Many of them live in lower-income households—37% live in households earning less than $30,000; a relatively large share are students, or are looking for jobs. It is a much more racially diverse group than most of the others, and a somewhat higher proportion of its respondents identify as liberal compared with the national rate.

- Lifestyle: This is a group heavily involved with technology, especially mobile devices: 82% access the internet with a mobile device such as a smartphone or tablet and 68% own smartphones. (However, they are more likely than several other groups to say that there is a lot of useful, important information that is not available on the internet.) Fully 86% of the internet users among them use social networking sites and 27% use Twitter, higher rates than most other groups. When it comes to reading, they are fairly typical: Young and Restless members read an average of 11 books in the past 12 months, and a median of 5.

- Relationship with libraries: The Young and Restless one of the most likely groups to say their library use has decreased in the past five years (36% say that), and just 11% know all or most of the services their library offers (compared with 23% of general population). At the same time, their views about the importance of libraries are generally positive: 71% agree that libraries promote literacy, and 61% agree libraries improve the quality of life in a community.

Rooted and Roadblocked (7% of the population)

- Overview: This group’s name derives from the fact that they are longtime residents of their communities, but may face many potential hurdles in their lives: 35% are retired, 27% are living with a disability, and 34% have experienced a major illness (either their own or that of a loved one) within the past year. It is the oldest group, with a median age of 58. Like other low engagement groups, they have used libraries at some point in their lives, but only a third went in last 12 months. Still, among the low engagement groups, they are the most likely to say that the closing of the local library would have a major impact on the community (61% say that).

- Who they are: Rooted and Roadblocked is the oldest group in the typology, with a large share of retirees and a small share of parents with minor children. It also includes a higher proportion of white (69%) when compared with other low or non-engagement groups. Adults in this group are somewhat less likely to have completed higher levels of education, with 21% having graduated from college (compared with the national benchmark of 27%).

- Lifestyle: The Rooted and Roadblocked are longtime residents of their communities, but less engaged with certain community activities—about half (52%) don’t regularly take part in any of the community activities we asked about. They have lower proportions of internet users (74%), home broadband adopters (58%), smartphone owners (40%), and social media users. They were also less likely to feel comfortable with technology-related tasks we asked about, and some 28% did not read a book in the past 12 months.

- Relationship with libraries: This group stands apart from the Not for Me group in its relatively positive views about the role of libraries in communities: 78% agree that libraries are important because they promote literacy and reading; 75% say libraries improve the quality of life in a community; and 72% say libraries give everyone a chance to succeed. Finally, though only 36% have a library card and just 33% visited a library in person in the past year, some 54% say library closing would affect them and their families in some way.

Non-engagement groups

Distant Admirers (10% of the population)

- Overview: Distant Admirers account for the majority of those who have never used a library. Despite their lack of personal library use, many say others in their house use libraries, and quite a few indicate that they indirectly rely on various library services. They have very high opinions about importance and role of libraries in communities, in sharp contrast to the other non-user group. As a group, they are relatively older and more likely to live in lower-income households.

- Who they are: In addition to having the largest share of Hispanics (27%) of any group, Distant Admirers include a somewhat higher proportion of men (56%) than the general population. They are also more likely to have relatively lower levels of education (62% did not attend college) and household income (42% live in households earning less than $30,000 a year).

- Lifestyle: They are less likely than some of the other groups to know many neighbors, and when it comes to engagement with cultural and other community activities, they participate at rates that are considerably below the national benchmark—48% say they do not regularly do any of the community activities we asked about. Their technology profile is notably below the national benchmark, and few are heavy book readers. They are much less likely than most other groups to read the news regularly, to feel they can find information on key subjects, and to say they like to learn new things.

- Relationship with libraries: Despite their lack of personal use of libraries, this group is notable for its generally positive views about libraries. This might stem from the fact that 40% of Distant Admirers report that someone else in their household is a library user. Two-thirds of them (68%) say libraries are important because they promote literacy and reading; 66% say public libraries play an important role in giving everyone a chance to succeed; 64% say libraries improve the quality of life in a community. Finally, 55% say the loss of the local library would be a blow to the community.

Off the Grid (4% of the population)

- Overview: Their name comes from the fact that they are disconnected in many ways—not only from libraries, but also from their neighbors and communities, from technology, and from information sources. Many do not regularly read books or stay current with the news, and their technology profile is the lowest among the groups. Their feelings about libraries are likewise distant: Just 28% say their library’s closing would have a major impact on their community, and another one in four (25%) say it would have no impact at all.

- Who they are: This group includes higher proportions of men (57%), older respondents (the median age 52), and Hispanic respondents (19%), and many tend to live in lower-income households and have lower levels of education—34% never completed high school. The vast majority of members of this group live in small towns (38%) and rural areas (45%), far more than most other groups.

- Lifestyle: Those in the Off the Grid group are longtime residents of their communities, but 38% say they don’t know the names of anyone who lives close by. They also engage in certain community activities at low levels, and just 59% say they socialize with family and friends daily (well below the national benchmark of 78%). Only 56% use the internet, and just 33% have smartphones. Half read no books in the previous 12 months, and just a quarter (25%) say they read books daily.

- Relationship with libraries: Like Distant Admirers, none of the members of this group have used a public library in their lives; unlike Distant Admirers, they have the least positive views about libraries. For instance, less than half (45%) strongly agree that public libraries play an important role in giving everyone a chance to succeed by providing access to materials and resources, a view that is otherwise shared by 72% of the general population.

General patterns in Americans’ engagement with public libraries

Some general trends extend through these findings, as documented in our earlier reports such as How Americans Value Public Libraries in Their Communities:

- Socioeconomic status: Broadly speaking, adults with higher levels of education and household income are more likely to use public libraries than those with lower household incomes and lower levels of education. However, among those who have used a library in the past year, adults living in lower-income households are more likely to say various library services are very important to them and their families than those living in higher-income households.

- Parenthood: Parents of minor children, compared with non-parents, are significantly more likely to use libraries and value libraries’ role in their lives.

- Ties to learning acquisition: Students, job seekers, and those without home internet, are especially likely to value particular library services.

These patterns are particularly prominent in the high engagement categories, which contain many of these (often overlapping) groups. In this way, high and medium engagement groups are often more alike than different. In contract, the low and non-engagement groups tend to be more distinct in the circumstances surrounding their lack of library engagement. For instance, looking only at low engagement groups (which include people who have used a library at some point in their lives but not recently), there are:

- Not for Me: Respondents who tend to dislike public libraries and are more likely to see them as irrelevant to modern life;

- Young and Restless: Young people who generally feel positively about public libraries, but are relatively new to their neighborhoods and are unlikely to know where their local library is located;

- Rooted and Roadblocked: Older adults who generally think libraries are good for their community, but may have obstacles in their lives, view libraries as somewhat difficult to use, or otherwise think that libraries are not personally relevant to them at this point in their lives.

Broader trends in Americans’ information habits

Though the main focus of this report is to describe the typology, there are a number of interesting thematic threads that emerge through that analysis:4

Americans’ library habits do not exist in a vacuum: People’s connection—or lack of connection—with public libraries is part of their broader information and social landscape. As a rule, people who have extensive economic, social, technological, and cultural resources are also more likely to use and value libraries as part of those networks. Many of those who are less engaged with public libraries tend to have lower levels of technology use, fewer ties to their neighbors, lower feelings of personal efficacy, and less engagement with other cultural activities.

Most Americans do not feel overwhelmed by information today. Some 18% of Americans say they feel overloaded by information—a drop in those feeling this way from 27% who said information overload was a problem to them in 2006. Those who feel overloaded are actually less likely to use the internet or smartphones, and are most represented in groups with lower levels of library engagement (such as Off the Grid, Distant Admirers, and Not For Me).

Life stage and special circumstances are linked to increased library use and higher engagement with information: Deeper connections with public libraries are often associated with key life moments such as having a child, seeking a job, being a student, and going through a situation in which research and data can help inform a decision. Similarly, quieter times of life, such as retirement, or less momentous periods, such as when people’s jobs are stable, might prompt less frequent information searches and library visits.

Acquiring information is often a social process in which trusted helpers matter: There are indications in the survey that people often feel they need their social networks and reliable experts to help them navigate some information-intensive activities. Even those in the most self-reliant groups, such as Library Lovers and Information Omnivores, say they would probably ask for help when they file their taxes, if they ever decided to start a business, or apply for government benefits. And the vast majority of those in lower engagement groups say they would likely ask for help if they wanted to master a new technology gadget or start using a new social media platform.

Technology use is not so much a substitute for “offline” activities as it is an enhancement tool: One of the persistent questions about the impact of digital technology is whether it pulls people away from traditional institutions and activities. In the case of library users, there is a strong tie between technology and library use. For instance, the technology-rich profiles of Information Omnivores might suggest that their gadgets could provide all the media and data they could possibly need—yet they still patronize libraries at high levels. Conversely, people with less technology in their lives, such as the Not For Me and Rooted and Roadblocked groups, are also less likely to use libraries. This suggests that technology is an “add on” for users that helps them leverage the way they acquire information.

Libraries score high ease of access and use—even among those who are not frequent users: Fully 91% of Americans ages 16 and older say they know where the closest library is, and 72% live within 5 miles of a library branch. Asked how easy it would be for them to use libraries if they wanted, 93% of Americans ages 16 and older say libraries would be easy for them to visit in person, including 74% of those in the Off the Grid group. Further, 82% of all Americans say library websites would be easy for them to use.

There are people who have never visited a library who still have positive views of public libraries and their roles in their communities: Members of the group we identify as “Distant Admirers” have never personally used a library, but nevertheless tend to have strongly positive opinions about how valuable libraries are to communities—particularly for libraries’ role in encouraging literacy and for providing resources that might otherwise be hard to obtain. Many Distant Admirers say that someone else in their household does use the library, and therefore may use library resources indirectly.